NICE amends Covid-19 critical care guideline after judicial review challenge

A proposed judicial review challenge to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (‘NICE’) COVID-19 guideline for clinical care has secured important changes to protect the rights of people with autism, learning difficulties and mental disorders from unjustified discrimination in access to critical care during the coronavirus pandemic.

The NICE Covid-19 guideline for critical care published in March 2020 are expressed to be mandatory for all clinicians in the NHS to implement.

The guidelines specify which patients will qualify for admission to hospital and referral to critical care, should their COVID-19 illness require this, and which patients will not be offered such treatment. NICE have decided the large number of patients likely to require critical care as a result of the pandemic are to be managed by the criteria set out in the guideline. The guidelines state that part of their purpose is to ‘enable services to make the best use of NHS resources’.

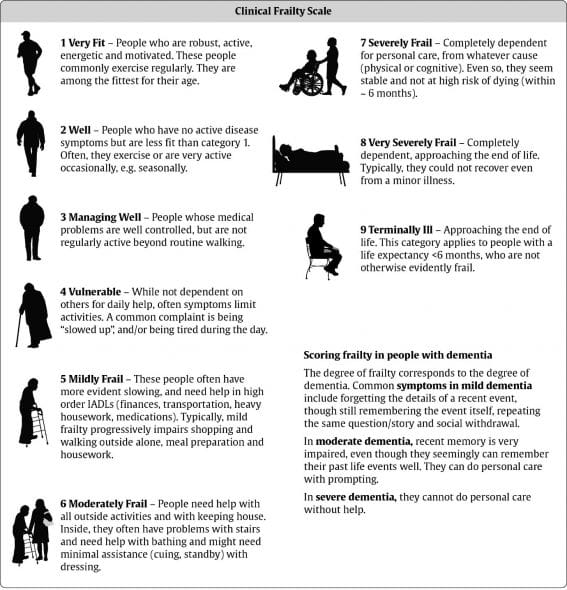

The original version of the guideline stated that on admission to hospital, an assessment was to be conducted for every adult against the following 9 point Clinical Frailty Scale for Frailty Assessment (‘CFS’).

There is no explanation in the guideline as to what frailty is. The British Geriatric Society explains that it is a concept linked to the ageing process and that it should be differentiated from disability.

As originally drafted, the guideline drew a clear distinction between the approach to be taken for those with a CFS score of less than 5 and those with a CFS score of 5 or more. For those with a CFS score of 5 or more, the guideline suggested it may not be appropriate to provide them with hospital treatment. This inference is explicit in an accompanying algorithm which shows that people in the first category will not pass through a period of ward based care before moving to critical care. Furthermore, the guideline states ‘Sensitively discuss possible ‘do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation’ decision with all adults with capacity and a CFS score suggestive of increased frailty (for example 5 or more)’. Again, this is clearly differential treatment of the cohort of adults with a CFS score of 5 or more compared with those whose score is less than 5, in that the former group will be more likely to have a decision that CPR should not be attempted.

Problems with the guidelines

In our view, the guidelines as originally drafted unlawfully discriminated against people with long-term disabilities, who are much more likely to be scored at 5 or above on the CFS than the general population due to their care needs, contrary to Articles 2,3, 8 and 14 ECHR and sections 19 and 29 of the Equality Act 2010.

Many healthy adults with autism and learning difficulties would likely be classified at 6 or 7 on the CFS. In particular, disabled people are much more likely to be scored 7 than non-disabled people, as it is only disabled people who will generally have total dependency for personal care. There was nothing originally in the guideline to explain that pre-existing disability should be treated differently to frailty, or that the reason for a person’s reduced ability to carry out the tasks and activities listed in the CFS is relevant to its application.

In our view there was no justification for the guideline as it was likely to result in significant numbers of disabled people being denied access to critical care on an erroneous basis.

In our view the guideline was published in breach of the public sector equality duty (‘PSED’) in section 149 of the Equality Act 2010 which requires public bodies to pay ‘due regard’ to the need to eliminate discrimination and advance equality of opportunity for disabled people.

In our view NICE also acted unlawfully by failing to consult with disabled people or their representative organisations at all in developing the guideline, even though the effects on such people were potentially devastating

The decision to publish the guideline in its original form was also arguably irrational in that NICE took a tool developed to address the needs of elderly people and sought to apply it without modification or adequate explanation to the entire adult population. The entirely predictable result of this was that younger disabled people risk being assessed as ‘Severely Frail’ because of their care needs when in fact critical care might be entirely appropriate for them.

As a result of these problems, Steve Broach and Victoria Butler-Cole QC of 39 Essex Chambers were instructed by Peter Todd of Hodge Jones & Allen to commence a claim for judicial review of NICE and their decision to adopt the Covid-19 guidelines. The concerns above were set out in a detailed letter before claim which was sent to NICE in accordance with the judicial review pre-action protocol.

Amendments

In light of the proposed legal challenge, NICE agreed to amend the guideline so that CFS should not be used in younger people, people with stable long term disabilities, learning disabilities, autism or cerebral palsy. Instead individualised assessment is recommended in all cases where the CFS is not appropriate

The critical change is the replacement of the use of the CFS with an ‘individualised assessment’ of frailty for the under 65s, including younger adults with autism or a learning disability. We understand this to mean that clinicians will assess an individual’s physical vulnerability to intensive care and their chances of survival on an individual basis and in light of their current presentation, without assuming that a long-term disability or care requirement is a reason not to offer treatment. We note that national guidance on prioritising patients is due to be published imminently, and will be scrutinising the new guidance carefully.

Our client’s litigation friend and mother said: ‘Whilst I welcome NICE’s amendments to the guideline, I remain deeply concerned that the guidelines were released in the first place without any consideration of the glaringly obvious, devastating implications for disabled people. This is yet another example of the systemic discrimination disabled people experience in the UK.’

Peter Todd, Partner at Hodge Jones & Allen, said: ‘Disabled people, in particular people with learning disability, autism and/or a mental disorder, are particularly at risk of poor health outcomes and discriminatory treatment by health services and NICE’s COVID-19 guideline for clinical care reinforced this. I am disappointed that NICE have taken such a high handed approach and have refused to enter into any discussions on the wording of the guideline to make it clearer for decision-makers. We strongly urge doctors to ensure that they comply with all relevant equality and human rights standards when they are taking decisions around prioritisation of treatment throughout the Covid-19 pandemic.’